By Trent Gilmore, 2021 Native Plant Intern with the Friends of Birmingham Botanical Gardens

There has been a lot of buzz over the past few years about honeybees (Apis mellifera). More people than ever have taken up the practice of raising bees for several reasons, the most obvious being the delicious honey they produce, but also because of increased interest in saving them.

This interest stems from the fact that we are facing what ecologists say is a pollinator crisis. Increased pesticide use and various pathogens have decimated honeybee populations. Although this is a serious issue, it’s not the decline in honeybees alone we need to worry about.

The honeybee is not the only bee that needs protection. Other bees we should be working to protect are our many species of native bees. Honeybees are not native to North America; they were imported from Europe. Some species of our native bees include mason bees (Osmia bicornis), leafcutter bees (Megachile sp.), bumblebees (Bombus sp.), orchard bees (Osmia lignaria), and sweat bees (Halictus sp.). These are the bees that pollinated our flora long before we imported honeybees.

Our native bees are vastly more efficient at pollinating than their non-native counterparts because of the way they “dance.” This “dance,” a special process known as frequency-dependent selection, is the result of thousands of years of coevolution among our native bees and our flora.

Many plants need to be cross-pollinated to set seeds. Some bees are more efficient in cross-pollinating than others. One of nature’s solutions for plants to get more “bang for their buck” was producing nectar only when it sensed specific frequencies from certain bees. Over thousands of years, bees evolved the ability to produce these frequencies by vibrating (dancing) when landing on a specific flower.

This technique is most commonly performed by bumblebees, which use hundreds of frequencies. Because they are not native, honeybees do not efficiently pollinate much of our native flora. Honeybees are good at pollinating cultivated foods we grow; however, they are not good at pollinating our many native plants that rely on frequency-dependent selection.

What can we do to keep our native bee population healthy and strong? Answers include using fewer chemicals and limiting habitat reduction. The most effective solution is to stop replacing their food sources with non-native plants. The No. 1 factor negatively impacting native bees is the spread of invasive non-native plants that bees cannot recognize or use efficiently. It’s not that we need to devote entire landscapes to natives, but by adding more native plants to our gardens, we provide better food sources for our bees.

Native plants that native bees love:

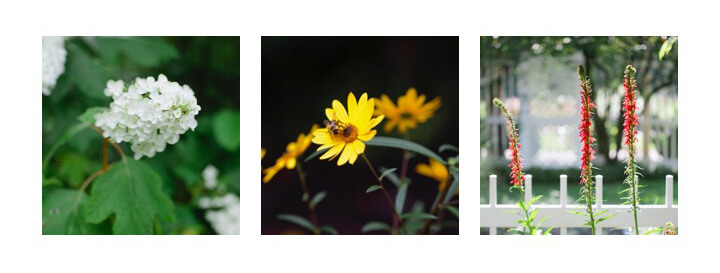

Oakleaf hydrangea (Hydrangea quercifolia)—intense fragrance, white flowers, flowers May–July

Eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis)—grows 20–30 feet tall, magenta blossoms in spring

Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis)—flowers June–September, blooms white and pink, good for bumblebees

St. John’s wort (Hypericum frondosum)—yellow, puffy blooms, flowers June-July, produces lots of pollen

Sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum)—flowers June–July, leaves turn crimson in the fall, leaf cutter bees enjoy them

Pickerelweed (Pontederia cordata)—aquatic nectar provider, flowers May–October, purple flowers

Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)—grows 3-4 feet tall, pink/purple flowers, flowers June–September

Foxglove beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis)—white flowers, 2–4 feet tall, semi-evergreen, flowers May–July

Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia sp.)—yellow flowers, flowers June–September, many choices

Golden Alexander (Zizia aurea)—yellow flowers, flowers March–June, good early pollen production

Butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa)—deep orange flowers, Monarch butterfly food source, flowers June–August

Rough goldenrod (Solidago rugosa)—abundant small yellow flowers, flowers August–October, helps build food storages for winter

Mountain mint (Pycnanthemum muticum)—grows 1–3 feet, does well in moist soil, has a silvery leaf, good pollinator spring–fall

Cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis)—big red spiral blooms, grows 2–4 feet, flowers July–September

When planting make sure to have an abundance of diversity. These are only some of the numerous native plants that support our native bees. A quick Internet search will give you access to many others.